Air Traffic Controller’s Negligence at Issue

US District Judge Florence-Marie Cooper determined that two tower controllers Edward Weber and Cynthia Issa made a series of negligent decisions that led to the cause of a Robinson R44 Helicopter crash killing pilots Robert Bailey and Brett Boyd and severely injuring Gavin Heyworth, a stident plot. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) agreed to pay $4.5 million in damages to Heyworth of the November 6, 2003 helicopter crash at Torrance Municipal Airport (TOA). Gavin Heyworth was taking a solo instructional flight in a Robinson R22 at the time of the accident. Heyworth survived the crash, but suffered severe and life changing injuries.

In the original NTSB report, the Board found the following took place. On November 6, 2003, at 1528 Pacific standard time, a Robinson R22 Beta II, N206TV, and a Robinson R44, N442RH, collided in midair while in the traffic pattern at Zamperini Field, Torrance, California. Pacific Coast Helicopters was operating the R22 under the provisions of 14 CFR Part 91. Robinson Helicopter Company was operating the R44 under the provisions of 14 CFR Part 91. The solo student pilot in the R22 sustained serious injuries. The certified flight instructor (CFI) and the private pilot undergoing instruction (PUI) in the R44 sustained fatal injuries. Both helicopters were destroyed; a post crash fire partially consumed the R44. The R22 departed on a local instructional flight about 1442. The R44 departed on a local instructional flight about 1449. Visual meteorological conditions prevailed, and no flight plans had been filed. The R22 came to rest between runways 29R and 29L; approximate global positioning system (GPS) coordinates of the primary wreckage were 33 degrees 48.275 minutes north latitude and 118 degrees 20.536 minutes west longitude. The R44 came to rest on the departure end of runway 29L; approximate global positioning system (GPS) coordinates of the primary wreckage were 33 degrees 48.277 minutes north latitude and 118 degrees 20.584 minutes west longitude.

The instructor for the solo student had been watching him during his flight. The student flew the R22 from its parking area between taxiways D and E to a helipad north of runway 29R. The student practiced on the helipad, and then completed several touch-and-go landings to the helipad. He requested a return to his parking area. Upon hearing this request, the instructor turned the volume of his radio down, and turned away to talk to a bystander.

One witness reported that the R44 was speeding up and increasing in altitude as it took off straight ahead on runway 29L. He first observed the R22 when it was over runway 29R, or slightly north of it. The R22 was starting to descend as it was transiting across the left runway to the southwest, and appeared to be heading toward its landing area.

Other witnesses pointed out that the R22 was above the R44. The R44 seemed to increase its climb rate just before the collision. The two helicopters collided about 50 feet in the air over runway 29L. The R22 spun left several times before it contacted the ground.

A National Transportation Safety Board specialist interviewed the controllers, and obtained recorded radar data. He prepared a factual report, and pertinent parts follow.

Because of technical difficulties with the recordings of the ATC voice channels, times in this report prior to 1523:02 are based on draft transcripts provided early in the investigation. Times after that are valid times.

The R22 pilot first called the LC1 controller at 1442 requesting to fly from the Pacific Coast Helicopters parking area to the North Pad. He did not indicate that he was a student pilot; the controller did not think that he was a student, because his radio technique was good. He flew to the North Pad, which is a helicopter-only practice landing point that is at midfield on the north side of runway 29R.

Pilots operating at the North Pad typically fly right closed traffic patterns at 600 feet msl. They are required to keep their pattern within the lateral confines of the runway 29R displaced thresholds. They are required to contact the LC1 controller for each circuit around the pattern, or if they wish to extend their pattern beyond the 29R threshold limits.

The R44 pilot contacted the LC1 controller at 1449, and requested a northeast departure from the “antennae site,” which is at the intersection of the ramp area and taxiway G. The LC1 controller cleared him for takeoff from runway 29R, and the pilot departed the airport area to the northeast. The R44 pilot returned at 1505; he reported 6 miles north of the airport, and requested to operate on the North Pad. The controller advised him that the pad was in use (by the R22), and asked the pilot if he wanted to use the runway instead. The pilot accepted, and the controller instructed him to report a 2-mile right base entry. At 1507, the controller provided a traffic advisory of a departing helicopter, cleared him for the option on runway 29R, and told him to enter right closed traffic. The pilot continued routine traffic pattern operations until 1525, including landings on runway 29L.

At 1523:14, the R22 pilot requested a North Pad takeoff and landing at PCH parking. PCH parking referred to the parking area used by Pacific Coast Helicopters. It is west of the tower, on the ramp between taxiways D and E. The controller instructed him to hold, and the pilot acknowledged holding. At 1524:33, the controller advised him that he could proceed in right traffic to the North Pad after a Cessna passed off his left. At 1524:56, the R22 pilot transmitted, ” takeoff and land PCH parking.” At 1524:59, the LC1 controller responded, “Helicopter six tango victor fly westbound.” Between 1525:18 and 1525:52, there was some confusion caused by the pilot of a departing helicopter (29M) who incorrectly used the call sign 2RH when requesting departure from the ramp area. The controller resolved the confusion.

At 1526:01, the controller cleared the pilot of the R44 to, “make your base your discretion two niner left cleared for the option”, and at 1526:15, in the same transmission, continued, “helicopter six tango victor make a right turn to the downwind.” At 1526:19, the R22 pilot acknowledged, but only with his call sign. At 1526:32, the controller again cleared the R44 for the option on runway 29L, and the pilot acknowledged.

At 1526:59, the controller advised the pilot of the R22, “ah you’re gonna cross midfield as soon as I get a chance.” At 1527:17, the controller instructed the R22 pilot to, “turn right,” and the pilot acknowledged with his call sign. At 1527:49, the controller transmitted, “Helicopter six tango victor runway two niner right cleared to land.” At 1527:53, the R22 pilot acknowledged with his call sign. At 1527:54, the controller transmitted, “turn right helicopter six tango victor runway two niner right cleared to land.” There was no communication from the R22 pilot. At 1528:12, the LC1 controller advised the R44 pilot, “robinson two romeo hotel caution for the helo oh.”

A review of recorded radar data showed a target that turned off the right downwind leg, crossed runway 29R, and approached runway 29L in the immediate area of the accident. The last target for this track was at 1528:10, approximately 2 seconds before the collision. A plot of this track on a street map indicated that it was perpendicular to the runways at 1527:49, and the target was between Lomita Boulevard and Skypark Drive. At 1527:54, this target was still approaching Skypark Drive and north of runway 29R. After crossing Skypark about 5 seconds later, the target appeared to turn toward the southwest, and the last two targets were approaching runway 29L at a shallow angle. Another target turned from right downwind to base to final for runway 29L. Its last target appeared at 1527:15; its track lined up with runway 29L, and was westbound abeam the approach end of runway 29R.

PERSONNEL INFORMATION

R22 Pilot

A review of Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) airmen records revealed that the R22 pilot held a student pilot certificate, and a first-class medical certificate issued in September 2003.

An examination of the student pilot’s logbook indicated that his first flight occurred on September 7, 2003. He had an estimated total flight time of 32 hours. He logged 16 hours in the last 30 days. He had solo time on two previous flights that totaled about 1.5 hours.

R44 CFI

A review of FAA airman records revealed that the pilot held a commercial pilot certificate with ratings for rotorcraft helicopter and instrument helicopter. He had a mechanic certificate with ratings for airframe and powerplant. He had a second-class medical certificate issued on October 3, 2003. It had no limitations or waivers.

No personal flight records were located for the CFI. The FAA indicated that the pilot reported that he had a total time of 8,900 hours on his last medical application.

R44 PUI

A review of FAA airman records revealed that the pilot held a private pilot certificate with ratings for airplane single engine land, multiengine land, and instrument airplane; he also had a helicopter rating. He held a second-class medical certificate issued on January 16, 2003. It had the limitation that the pilot must wear corrective lenses.

No personal flight records were located for the PUI. The FAA indicated that the pilot reported that he had a total time of 370 hours on his last medical application. An application for the Robinson safety course indicated that he had 52 hours in rotorcraft; all were in this make and model.

AIRCRAFT INFORMATION

R22

The helicopter was a Robinson R22 Beta II, serial number 2753. A review of the helicopter’s logbooks revealed that it had a total airframe time of 2,974.6 hours. The logbooks contained an entry for an annual inspection dated February 1, 2003. A 100-hour inspection occurred on October 30, 2003, and the helicopter accumulated 23.9 hours since its completion. The Hobbs hour meter read 2,974.6 at the accident site. The time since an airframe overhaul was 783.7 hours.

The engine was a Textron Lycoming O-360-J2A, serial number L-32698-36A. Total time recorded on the engine was 1,976.2 hours, and time since major overhaul was 789.3 hours.

R44

The helicopter was a Robinson R44, serial number 0002. A review of the helicopter’s logbooks revealed that the helicopter had a total airframe time of 1,046.5 hours. The logbooks contained an entry for an annual inspection dated April 3, 2003. It had a 100-hour inspection on July 15, 2003. It accumulated 74.7 hours since that inspection.

The engine was a Textron Lycoming O-540-F1B5, serial number L-25143-40A. Total time on the engine was 2,672.5 hours, and time since major overhaul was 479.1 hours.

COMMUNICATIONS

Both helicopters were in contact with the Torrance airport traffic control tower (ATCT) on frequency 135.6.

AIRPORT INFORMATION

The Airport/ Facility Directory, Southwest U. S., indicated that runway 29L was 3,000 feet long and 75 feet wide. The runway surface was asphalt. Runway 29R was 5,001 feet long and 150 feet wide. The runway surface was asphalt and concrete.

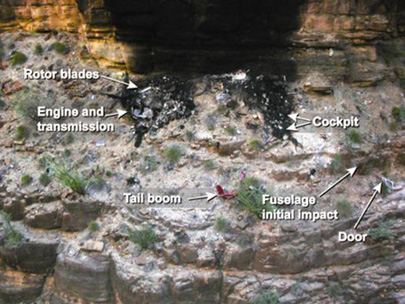

WRECKAGE AND IMPACT INFORMATION

The FAA and Robinson were parties to the investigation. Investigators from the Safety Board and the parties examined the wreckage at the accident scene.

The debris field was on runway 29L, and extended over 500 feet. The first identified debris (FID) pieces were shards of Plexiglass and R44 main rotor blade. A section of one R44 main rotor blade was 135 feet from the FID, and another piece was about 145 feet. The tip cap from this blade was at 174 feet.

A piece of R22 lower frame was 234 feet from the FID. The main wreckage of the R22 was at 270 feet, and about 70 feet north of the runway. About the same distance and another 120 north was a piece of R44 spar. Another piece of R44 spar was on the runway at 412 feet.

The main wreckage of the R44 came to rest inverted at 495 feet and about 25 feet right of the runway centerline. The left skid of the R44 was at 515 feet, and just off the right edge of the runway.

The last piece of debris was the main rotor of the R44 at 525 feet and near the runway centerline. One entire blade was present; it exhibited a wavy appearance, and buckled in several places. It had a scrape mark that was 2 inches wide across half of the blade chord (from the leading edge) and 36 inches from the tip. This scrape was dimensionally similar to the aft right strut of the R22. The second blade fractured and separated about 2.5 feet from the rotor hub; the fracture ran chordwise from the leading edge back to the trailing edge doubler, with the doubler remaining intact. The blade bent aft about 120 degrees at this point. The next 4.5 feet of blade exhibited some buckling. The rest of the honeycomb/skin section of the blade separated, as did the outboard 4.5 feet of spar. Two pieces of this blade, one being about 1.5 feet with the tip weights (3.5 pounds), and the other being the tip cap, were in the R22’s engine compartment behind the left pilots seat.

The R22 exhibited rotational scoring on the fan shroud, on the fan itself, and the tail rotor drive shaft twisted.

MEDICAL AND PATHOLOGICAL INFORMATION

The Los Angeles County Coroner completed autopsies of both pilots in the R44. The FAA Bioaeronautical Sciences Research Laboratory, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, performed toxicological testing of specimens of the pilots.

Analysis of the specimens for the CFI contained no findings for tested drugs in the liver. They did not perform tests for carbon monoxide or cyanide. The report contained the following findings for volatiles: no ethanol detected in muscle; 28 (mg/dL, mg/hg) ethanol detected in the brain; 11 (mg/dL, mg/hg) methanol detected in muscle; 212 (mg/dL, mg/hg) methanol detected in the brain; and 30 (mg/dL, mg/hg) of 2-butanol detected in the brain. The report stated that the ethanol found in this case might potentially be from postmortem ethanol formation, and not from the ingestion of ethanol.

Analysis of the specimens for the PUI contained no findings for carbon monoxide, cyanide, volatiles, and tested drugs.

TESTS AND RESEARCH

The aft strut of the right skid of the R22 separated about 1-foot from the bottom of the skid, with the skid placed in its approximate installed orientation. The fracture surface was relatively flat, and the round tubing bent inboard. The right side of the engine exhibited crush damage to the mid portion of the rocker covers and valves that was similar in dimension to an R44 rotor blade. The narrow band of damage continued around to the accessories between the engine and cabin. Tubing in this area and the back of the front seat exhibited fractures across a similar plane. A section of rotor blade from the R44 was imbedded in the lower left side of the R22 near the battery, which was behind the front left seat.

Robinson personnel provided the following information.

The radius of the R44 rotor, from the centerline of the hub to the tip is 198 inches. The distance between the aft strut and forward strut of the R22 is 50.5 inches (centerline to centerline). The distance between the left and right struts on the R22 (at the level of the first contact point) is 55 inches centerline to centerline).

Based on unique impact markings and color transfers, the Robinson air safety investigators opined that first R44 blade hit the center of the aft right strut of the R22, 36 inches from the tip of the blade, cutting through the strut without hitting anything else. The second R44 blade hit the R22 across the valve covers of the engine, 29 inches higher then the first hit. The blade fractured and separated about 48 inches from the tip. This blade also made contact with the engine cooling fan and scroll. The tip of this blade struck the cabin of the R22, 48 inches forward of the aft strut (12 inches of movement from the first blade hit to second blade hit).

This information could not yield a collision angle; however, it placed the R22 above, slightly forward of the R44, and on a similar course.

Visibility Study

The IIC and Robinson investigators examined exemplary helicopters at the Robinson factory. Pilots of the approximate height of the R44 pilots sat in an R44. Looking forward, they could see as high as the outboard 8 feet of the main rotor blade. Looking to the right, they could see eye level and no higher. They could see nothing aft. A pilot of similar height to the R22 pilot sat in the right seat of an R22. He could see about 10 degrees aft with the left door not installed. With it installed, he could only see abeam his seat, and no higher than eye level. The accident R22 had the door installed.

There were several procedures for helicopters to return from the helipad to the parking ramp. One controller stated that helicopters could travel directly across both runways, and land on the ramp if there was no conflicting traffic. The next method was to land on runway 29R; then the controller would clear the pilot to hover taxi across the runways to the ramp. A third method was to have the pilot cross both runways at midfield, land on taxiway A, and then taxi to the ramp.

The student pilot’s flight instructor described the procedures for returning to the ramp from the North Pad. One method was to request a direct air taxi crossing both runways and taxiway A. A second method was to depart west on the up wind. After reaching pattern altitude at the end of runway 29R, the controller would clear the pilot for a left turn to the south. After crossing Airport Drive, the pilot could turn downwind, fly east to the east “tees,” turn left to base, and then turn left to final for taxiway A or runway 29L. A third method was to take off to the west to pattern altitude, make a right crosswind turn, and then turn to a right downwind until abeam the east end of the 29R threshold. Here the pilot would turn right base and right final for either taxiway A or 29L. A fourth method was to take off to the west, make a right crosswind, make a right downwind to midfield, make a right turn to cross both runways at midfield, turn left to a left downwind for 29L, and then left base and final to either taxiway A or 29L.

The LC1 controller stated that he intended to have the R22 pilot depart the pad westbound along runway 29R, turn right to the downwind, and then turn right and land on 29R. He would then clear the pilot to hover taxi along taxiway C to the ramp. As the R22 passed the North Pad area as it traversed eastbound on the downwind leg, he instructed the pilot to turn right. There was no response, and the helicopter did not turn. A few seconds later, he cleared the pilot to turn right and land on 29R. He did not hear an acknowledgement, so he repeated the instruction. The R22 turned at that point. The controller saw the R22 north of the approach end of 29R with the nose pointed roughly at the tower. He then looked away to his radar display as he worked another aircraft. After talking to that aircraft, he decided to advise the R44 that the R22 would be landing on 29R abeam the R44 as it departed. He looked back just as the helicopters collided.

The Safety Board investigator-in-charge (IIC) released the R22 wreckage to the owner’s representative on February 12, 2004. The IIC released the R44 wreckage to the owner’s representative on April 30, 2007.

**This narrative was modified on May 14, 2007.

Contact a Helicopter Lawyer

If you have been injured or a loved one has been killed in a helicopter crash, then call us 24/7 for an immediate consultation to discuss the details of the accident and learn what we can do to help protect your legal rights. Whether the accident was caused by negligence on the part of the helicopter owner, hospital or corporation, the manufacturer or due to lack of training, poor maintenance, pilot or operator error, tail rotor failure, sudden loss of power, defective electronics or engine failure or flying in bad weather conditions, we can investigate the case and provide you the answers you need. Call Toll Free 1-800-883-9858 and talk to a Board Certified Trial Lawyer with over 30 years of legal experience or fill out our online form by clicking below: