Helicopter Collides with Grand Canyon Wall

On September 20, 2003, about 1238 mountain standard time, an Aerospatiale AS350BA helicopter, N270SH, operated by Sundance Helicopters, Inc., crashed into a canyon wall while maneuvering through Descent Canyon, about 1.5 nautical miles (nm) east of Grand Canyon West Airport (1G4) in Arizona. The pilot and all six passengers on board were killed, and the helicopter was destroyed by impact forces and postcrash fire. The air tour sightseeing flight was operated under the provisions of 14 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 135. Visual meteorological conditions (VMC) prevailed for the flight, which was operated under visual flight rules on a company flight plan. The sightseeing / tourist helicopter was transporting passengers from a helipad at 1G4 (helipad elevation 4,775 feet mean sea level [msl]) near the upper rim of the Grand Canyon to a helipad designated “the Beach” (elevation 1,300 msl) located next to the Colorado River at the floor of the Grand Canyon.

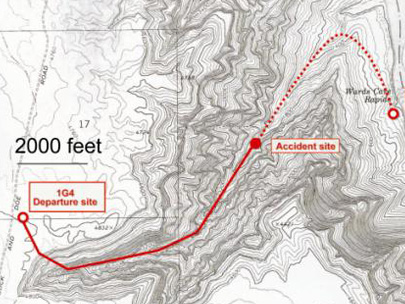

About 0745, the accident pilot flew the accident helicopter on an operational check flight at the company’s base at McCarran International Airport (LAS), Las Vegas, Nevada. After the short local flight, Sundance ground personnel (consisting of loaders and a tour coordinator) boarded the helicopter about 0840 and flew with the accident pilot on a 45-minute flight from LAS to 1G4 to commence the day’s Descent Canyon tour operations. The director of operations estimated that each flight from 1G4 to the Beach helipad lasted about 3.5 minutes (see figure 1).

Figure 1. Topographic chart showing the 1G4 departure site, the accident site, and the prescribed route through Descent Canyon to the Beach helipad.

These tourist flights were part of an advertised tour package in which Sundance pilots flew passengers through Descent Canyon, dropped them off at the Beach helipad for a scenic boat ride on the Colorado River, then picked them up at the Beach helipad later in the day for a return flight to 1G4 through another scenic canyon.

The accident flight was the pilot’s 11th flight through Descent Canyon that day. The tourist / sightseeing helicopter lifted off from 1G4 about 1237 and flew to the rim of Descent Canyon. The tour coordinator stated that she did not hear the pilot make either the first customary radio call stating that he was lifting off from the helipad or the second customary radio call advising that he was entering Descent Canyon en route to the Beach helipad. A pilot for Papillon Grand Canyon Helicopters, who departed in his helicopter from 1G4 and flew through Descent Canyon about 2 minutes before the accident flight, stated that he did not hear any radio calls from the accident pilot and did not know that a helicopter was behind him in the canyon.

The Sundance tour coordinator and a Papillon loader at 1G4 stated that they observed the accident helicopter hover at the rim of Descent Canyon for about 30 to 45 seconds before beginning a level descent. They stated that the helicopters usually flew directly from the loading pads to the top of Descent Canyon and either nosed down into the canyon or hovered for only a few seconds before descending nose-low into the canyon. The Sundance tour coordinator stated that ground personnel assumed that the accident pilot may have been waiting for the Papillon helicopter to clear the canyon before he initiated his descent.

The Papillon pilot who descended his helicopter ahead of the accident flight stated that, while he was approaching the helipad next to the Colorado River, he noticed a fireball rising on the canyon wall behind him in Descent Canyon. There were no known witnesses or air traffic control radar data to provide information on the accident flight’s progress inside the canyon after it descended out of view of the witnesses at 1G4.

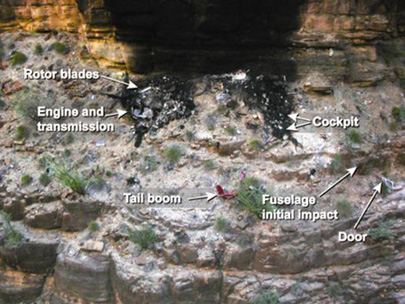

The main wreckage was located on a canyon wall ledge about 400 feet beyond a near?vertical canyon wall that showed evidence of gouging consistent with a main rotor blade strike (see figure 2).

Figure 2. Initial main rotor blade impact location and main wreckage location. Note: This photograph was taken by a National Transportation Safety Board investigator on February 4, 2004, during a canyon topography documentation flight. The wreckage was previously removed from the site.

Figure 3. Overview of initial main rotor blade impact location, main wreckage location, and prescribed route of flight. Note: This photograph was taken by a Safety Board investigator on February 4, 2004, during a canyon topography documentation flight. The wreckage was previously removed from the site.

Figure 4. Main wreckage debris field.

SOURCE: NTSB

Contact a Helicopter Lawyer

If you have been injured or a loved one has been killed in a helicopter crash, then call us 24/7 for an immediate consultation to discuss the details of the accident and learn what we can do to help protect your legal rights. Whether the accident was caused by negligence on the part of the helicopter owner, hospital or corporation, the manufacturer or due to lack of training, poor maintenance, pilot or operator error, tail rotor failure, sudden loss of power, defective electronics or engine failure or flying in bad weather conditions, we can investigate the case and provide you the answers you need. Call Toll Free 1-800-883-9858 and talk to a Board Certified Trial Lawyer with over 30 years of legal experience or fill out our online form by clicking below: